Bat Masterson

The Legend

The noted gambler, later lawman, Bat Masterson surveyed the town of Mobeetie about 1876. Born William Barclay Masterson in 1853, he was a buffalo hunter, United States Army Scout, surveyor, lawman, and finally a journalist. After fighting in the Battle of Adobe Walls in 1874, he scouted for Colonel Nelson A. Miles during the Red River War. In 1875-1876, Masterson lived at Mobeetie and worked as a faro dealer in Henry Fleming's saloon. During a gunfight with Sergeant Melvin A. King over a card game and a dance hall beauty, Mollie Brennan, Bat killed King. Bat was shot in the pelvis with a bullet fired by King that had passed through Mollie's body, killing her. The injury caused Masterson a permanent limp. He soon returned to Dodge City, Kansas where he was a lawman for many years. Masterson later moved to Denver and eventually to New York City where he was a sports writer for the "Morning Telegraph". He died at his desk in 1921 at age 67.

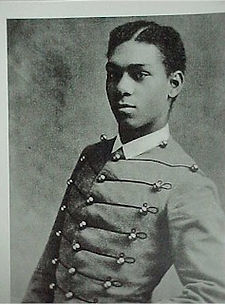

Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper

The First African American Graduate of West Point

Henry O.Flipper was West Point's First Black Graduate and America's First Black Officer. He was stationed at Fort Elliott, Texas in 1879.

Henry Ossian Flipper was born a slave on March 21, 1856, in Thomasville, Georgia. He began his education in a woodshed where an old slave taught him the alphabet. After the Civil War, his father, a skilled shoemaker and carriage trimmer, prospered and hired the wife of a former Confederate captain to tutor Henry and his other three sons. In the fall of 1872, Henry learned about a vacancy at the West Point Military Academy. After passing the qualifying examination, Flipper received his appointment on May 25, 1873.

Flipper became the first black graduate from West Point on June 14, 1877, after enduring four years of loneliness and isolation among the predominantly white cadets who, from time to time, harassed and mistreated him. When Flipper was handed his diploma, he received a standing ovation from his classmates and the spectators for his four years of dedication and courage. Major General John Schofield, West Point's Superintendent, gave a tribute to Flipper's bravery against isolation and exclusion by his classmates. He stated, "No white cadet had ever been burdened with the hope of an entire race on his shoulders. Anyone knows how quietly and bravely this young man--the first of his despised race to graduate from West Point--has borne the difficulties of his position; how for four years he has had to stand apart from his classmates as one with them but not of them... ." Henry O. Flipper became the first black officer in the United States Military Service.

Flipper was commissioned a Second Lieutenant and was assigned to frontier duty with the all black Tenth United States Cavalry at Fort Sill, Oklahoma (Indian Territory). The Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry became known as "Buffalo Soldiers." They fought Apache and Comanche warriors and policed rustlers and outlaws. Buffalo Soldiers built new roads and telegraph lines and protected stagecoaches. Perhaps the Plains Indians dubbed them "buffalo soldiers," because their hair seemed similar to a buffalo's or it may have been a term of respect, since the buffalo played an integral role in the life of the Plains Indians.

Flipper became a close friend of his troop commander, Captain Nicholas Nolan, an Irishman, who took the young Lieutenant under his wing. When Nolan married, he brought his new bride and her sister back to live on the post. After Captain and Mrs. Nolan insisted that Lt. Flipper board with the Nolan family, Flipper discharged his cook and moved in with the Nolans. He and Miss Mollie Dwyer eventually became close friends and often went riding together.

In early 1879, Troop A was ordered to Fort Elliott, Texas, where Captain Nolan, was made the commanding officer. He appointed Lieutenant Flipper to be his adjutant which was the ranking officer on the Commanding Officer's staff. In addition to his adjutant duties, Flipper found time to map and survey the post and to help build a telegraph line from Fort Elliott to Fort Supply in Indian Territory. Flipper was included in all the social affairs at Fort Elliott. He usually declined invitations to picnics and dances, preferring instead to spend his leisure time riding with Mollie Dwyer. On Sundays, Lt. Flipper and Mollie joined other officers and their ladies chasing coyotes and jackrabbits on the plains. It was great sport, something like fox chasing in England.

Friendships and loyalties grew between the military and the pioneer families. One incident in the fall of 1879 involving military and civil authorities of Fort Elliott and Wheeler County reflects that relationship.

A federal marshal named Norton, armed with blank warrants, was sent from the Dallas federal courts to the Panhandle. The marshal arrested persons whom he suspected of selling tobacco without paying a federal tax or having a merchant's license. Since most ranchers maintained a supply of personal items such as tobacco products for sale to the cowboy employees, it was not difficult for the marshal to find violators. Norton arrested more than a dozen ranchers from all over the region and took them to Mobeetie where he arranged to have them tried by County Judge Emanuel Dubbs. The recently elected, untrained Dubbs, feeling the ranchers to have been mistreated, acquitted all of those charged. Marshall Norton, enraged by the acquittals, arrested Judge Dubbs and re-arrested the tobacco tax violators. Other county officials interfered and were also arrested. Norton, having arrested all the county officials, took them and the ranchers to Fort Elliott for safe keeping when other citizens threatened violence. There were no officials anywhere in the area with authority to do anything about the arrests. The only authorities not under arrest were those of the military at Fort Elliott and Marshal Norton himself.

Captain Nicholas Nolan, 10th Cavalry, post commander at the time, probably felt an undeniable allegiance to Norton, a federal government representative. He allowed some, and probably all, of the eighteen prisoners to be put in the Fort Elliott guardhouse.

Feeling considerably less allegiance to Marshal Norton, Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper, 10th Cavalry, reputed to have been the first Negro graduate of West Point and a rather independently minded officer, during the night released all of the civilian prisoners from the guardhouse. He loaded them into a wagon and was personally escorting them to safety in the Indian Territory when either Marshal Norton captured the party or the escapees decided to turn back and find a better way of solving the problem. Norton, one source reported, took Judge Dubbs, Lieutenant Flipper and Captain Nolan to Dallas where the two army officers were tried and fined one thousand dollars each for interfering in the processes of law. Dubbs was released without fine, and Marshal Norton was reprimanded.

In November, Flipper's troop returned to Fort Sill. For four months, Henry served as acting captain of Troop G of the 10th Cavalry until the troop's captain, Captain Lee, returned. Captain Lee, a close friend of Flipper's, was one of General Robert E. Lee's cousins who had chosen to serve on the Union side during the Civil War.

In 1880, Lt. Flipper was transferred to Fort Davis with his company where he became the post quartermaster and the acting "commissary of subsistence," which meant that he was in charge of housing, supplies, and equipment for the entire fort. After each transaction, Flipper detailed how his supplies were used and how much money was spent. Within months of receiving his new responsibilities, Flipper was receiving praise from his fellow officers for his handling of his commissary duties. Even the local merchants liked the way the young, black lieutenant did business; he was honest and trustworthy.

Trouble for the young Lieutenant was on the horizon in early January of 1881. Flipper was still continuing to ride with his dear friend Mollie Dwyer. However, Flipper was aware of a growing jealousy among several officers over his unique relationship with Miss Dwyer. First Lieutenant Charles Nordstrom, seemed particularly jealous and eventually wooed Miss Dwyer away from Flipper.

The next blow came in March when Colonel Shafter took over command of the fort. Shafter had a reputation for harassing any officers he disliked. Almost immediately, Shafter stripped Lieutenant Flipper of his quartermaster duties and informed him that he would soon be replaced as commissary officer as well.

Shafter then asked Flipper to move the commissary funds from the quartermaster's safe to Flipper's quarters. It was an unusual request, but the lieutenant complied with the colonel's wishes. Four months later, in July, as Henry was going over his commissary statements, he discovered a shortage of $2047.26. Although he knew that two to three hundred dollars were owed by various soldiers, he had no idea where the rest of the money had gone.

He later explained, "I was afraid to consult the Commanding Officer or any other officer of the post, because of my peculiar situation, because I had heard frequent stories from civilians about the post that the officers there were plotting to get me out of the Army, and because I had seen ... other officers prowling around my quarters at unseemly hours of the night. I so conducted myself as to be perfectly secure against any of their attacks. Up to that moment I never dreamed that anything was wrong with my commissary funds beyond the discrepancy of $200 or $300."

Henry Flipper suspected foul play, but decided to keep the matter to himself, resolving to make up the difference with his own money. His plan almost succeeded. However, while Flipper was waiting for a check from his book publisher to cover the missing funds, the chief commissary of the Department of Texas contacted Shafter, asking why July's money had not been deposited as usual in the bank in San Antonio. Colonel Shafter decided to investigate.

On August 13, 1881, Shafter sent two officers to Henry Flipper's quarters to search for the missing commissary funds. As the officers rifled through his personal belongings, Flipper stood by helplessly. When the officers were done, they seized commissary statements and checks, along with Flipper's West Point class ring.

Later that evening, Shafter accused the army's only black officer of embezzling government funds and arrested him, confining Flipper to the felons' cell in the guardhouse. The cell was so tiny that the "slats of the bunk had to be cut off to permit it to go in." Colonel Shafter prohibited anyone from visiting the cell without his approval, and at first he denied Lieutenant Flipper bedding, books, and writing materials.

Word soon spread throughout the settlement about Henry Flipper's incarceration, and the residents quickly began collecting money to cover the missing funds. By the morning of August 15, almost $1,700 had been collected. When three friends were allowed to visit Flipper later that day, he learned of the townspeoples' generosity and their belief that he was innocent of any wrongdoing.

Colonel Shafter hinted that if Flipper's friends were able to collect enough money, he might drop all charges. Full restitution of the $2,047.26 was quickly made, and Henry Flipper was released to his quarters on August 17, four days after his arrest.

After being released from the guardhouse, he was contained in his quarters, which were barricaded, nailed up, and made as secure as the guardhouse, and was guarded day and night by an armed sentinel. Flipper discovered that while he had been locked in the guardhouse, his quarters had been further searched, and several personal items had been taken. Shortly afterward, even though all the missing money had been repaid, Shafter brought court-martial charges against the second lieutenant.

When the court-martial convened on September 17, 1881, in the Fort Davis chapel, Henry Flipper found himself with no representation and facing a ten-member court-martial board, three of whom worked directly under Shafter. Lieutenant Flipper quickly asked for a temporary postponement so that he could raise money to hire a lawyer for his defense. A delay was granted.

Henry soon discovered that no lawyer would take his case for less than one thousand dollars, so he sent a white friend east to try to raise money for his defense. In Washington, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, his friend met with the leading African Americans of the day and explained all the details of Henry's case. However, no one offered to help.

Time was running out, when, as Flipper later wrote, "like a bolt out of a clear sky, I received a letter from Captain Merritt Barber of the 16th U.S. Infantry, white, offering to come and defend me. I had never seen or heard of him before, but . . . I accepted his offer at once, especially as I knew it would cost me nothing, officers not being allowed to charge anything for defending another." The Captain came to Fort Davis and lived with Flipper and made a brilliant defense. But Flipper was doomed.

The court-martial lasted until December, with Barber successfully bringing forth a string of witnesses testifying to Lieutenant Flipper's integrity, while also exposing inconsistencies in the prosecution's case. The lack of physical evidence proving embezzlement and Colonel Shafter's continued contradictions of his own testimony aided Flipper's case. Barber attributed the disappearance of the funds to Flipper's inexperience in financial matters, stating that "under Shafter's lax command,' his responsibilities were too much for Flipper to assume alone.

Nevertheless, the court found Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper not guilty of embezzlement but guilty "of conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman," and sentenced him to be "dismissed from the service of the United States." It was a harsh sentence. In two prior cases involving white officers who were found guilty of embezzlement, neither officer was dismissed nor dishonored.

Henry Flipper's case was reviewed by several high-ranking officials, one of whom recommended to the Secretary of War that Flipper's sentence be reduced to a lesser punishment. The Secretary of War agreed and sent word to President Chester A. Arthur recommending a lighter sentence. However, for some unknown reason, the president ignored the plea for leniency, and on June 24, 1882, he confirmed the court's original decision to dismiss Lieutenant Flipper from the army. Six days later, Second Lieutenant Henry Flipper was dishonorably discharged.

Disgraced, Flipper sold his horses and army equipment and went to El Paso. He soon found temporary work in a steam laundry, while he attempted to adjust to his new life. "I was thoroughly humiliated, discouraged, and heart-broken at the time," Flipper later recalled. "I preferred to go forth into the world and by my subsequent conduct as an honorable man and by my character disprove the charges." This Flipper did and, ironically, probably achieved out of the military more than he could have achieved had he remained in the military.

Though born a slave, Flipper achieved many "firsts" for a black American: West Point Academy graduate, cavalry officer, surveyor, cartographer, civil and mining engineer, translator, patented inventor, editor, author and special agent for the Justice Department. As assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, he was responsible for the planning and construction of the Alaskan railway system.

Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper made many contributions to the Forts at which he was stationed with his engineering skills that improved frontier life. The Forts at which he served include Fort Sill, Fort Elliott, Fort Concho, and Fort Davis. He has been honored with a permanent display and a statute in the West Point Library and a "Henry O. Flipper Day" on February 10 with an annual award to be given in his name. Flipper's Ditch, a project designed by Flipper to drain ponds at Fort Sill which caused the spread of malaria from which the soldiers became ill and often died, was declared a National Historic Landmark almost a century later on October 27, 1977. A large bronze marker commemorates Flipper's Ditch at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. A monument to Flipper's Buffalo Soldiers proposed by Gen. Colin Powell opened in 1992 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the birthplace of the 10th Cavalry. General Colin Powell, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff kept a painting in his Pentagon office featuring Lieutenant Flipper and his commanding officer, Colonel Grierson on patrol. When Colonel Grierson relinquished command of the 10th Cavalry in 1888, he stated, "The soldiers have cheerfully endured many hardships, and in the midst of great dangers steadfastly maintained a most gallant and zealous devotion to duty. They may rest assured that such valuable service to their country cannot fail, sooner or later, to meet with due recognition and reward."

"Frency" McCormick

"No one will ever find out who I am!"

A Mobeetie Character

A blue eyed, black haired Irish dance-hall girl who came to Mobeetie in 1880 from Dodge City. Little is known of "Frenchy's" origins since she had already acquired her name from cowboys at Fort Dodge, Kansas because of her Louisiana background and her ability to speak French fluently. She was born in 1852 near Baton Rouge, LA and she ran away at about 14 or 16 years of age. It has been said that when her mother died in Baton Rouge, Frenchy accompanied her father up the Mississippi on his steamboat to St. Louis where she quarreled with him about her love of dancing. Frenchy danced on the burlesque stage and in the famous Benedict Bar. When her father stopped her dancing, she caught a stage to Dodge City. Others say she ran away from a convent school in Baton Rouge to St. Louis with a man who abandoned her. All who knew her in later years agree that she had an above average education, a certain refinement and her handwriting was a beautiful script. While working in the dance halls and bars of Dodge, the beautiful but nameless girl was popular with the cowboys who named her "Frenchy".

Frenchy heard that to the south in the Texas Panhandle, there were herds of buffalo hunters and cowboys, and Mobeetie near Fort Elliott was a prosperous soldier town. She packed her beautifully elaborate dance dresses, plumes, satin slippers; smart floor length costumes and caught the stage for Texas.

In Mobeetie, she met Mickey McCormick, an Irish gambler, hunter and livery stable owner from Tascosa. She quickly became his good luck charm at the gaming tables and they were married in 1881. The name Frenchy gave for the license was Elizabeth McGraw and that was the same name she gave 56 years later when she applied for her state old-age pension. Her marble tombstone at Tascosa reads Aug. 11, 1852 - Jan. 12, 1941.

Billy Dixon

Buffalo Hunter & Scout

Born in Ohio County, West Virginia on September 25, 1850. Orphaned at the age of twelve, Dixon headed West. Over his 63 years he was a farmer, woodchopper, teamster, fur trapper, buffalo hide hunter, scout and guide for the U.S. Army during the Red River Indian War of 1874, storeowner and business man, cowboy, justice of the peace, and postmaster. Dixon was a hero of the Battle of Adobe Walls and was one of two civilians to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his courage during the Battle of Buffalo Wallow in the Red River War. He died March 9, 1913.

Mobeetie Founding Fathers

Pictured in the photo left to right:

Top row: Joe Mason, G W. "Cap" Arrington, Cape Willingham

Bottom row: N. F. "Newt" Locke, Emanuel Dubbs, Johnnie Long

Emanuel Dubbs

Emanuel Dubbs was the first County Judge in the Texas Panhandle, and served Wheeler County as judge for eleven years. Born on a farm near New Franklin, Ohio on March 1, 1843, Dubbs was a Civil War hero. After the war he went into the lumber business in Indiana until he was burned out with no insurance. He and his wife headed west to hunt buffalo where he was involved in the Indian Wars during the time of Adobe Walls. He came to Wheeler County in 1878 and "nested" in a valley nine miles east of Fort Elliott. He built a home from cottonwood logs as well as the furniture in the cabin. When the county organized in 1879 he was elected to the office of County Judge. The first court sessions were held in a former saloon when Dubbs came to town to sell milk, butter, and vegetables to Fort Elliott and the town people of Mobeetie.

J. J. "Johnnie" Long

J. J. "Johnnie" Long was one of the Panhandle’s outstanding citizens. A teamster with the United States Army, he was with Custer in 1873 on the Yellowstone Expedition, Nelson A. Miles in the Red River War of 1874, and Mackenzie in Colorado during the Ute uprising. While at Fort Elliott he was the teamster sent to cut cedars at Antelope Hills, Indian Territory from which the flagpole was constructed. When the fort was abandoned, he purchased the pole for $7.50 and raised it in front of his store in Mobeetie where he was a banker and merchant. He also built and operated the first cotton gin in the Panhandle.

Interview with Olive King Dixon

Fort Worth Star Telegram

Sunday, February 23, 1936

G. W. "Cap" Arrington

Cap Arrington served as Wheeler County Sheriff for eight years. Born December 23, 1844 in Alabama, he died March 31, 1923. His real name was John Cromwell Orrick, Jr. He changed his name to George Washington Arrington during the Civil War where he was a daring scout in Colonel Mosby’s Command. He was also Captain of Company C of the Texas Rangers before settling in Wheeler County. His jurisdiction as sheriff covered the entire Texas Panhandle where he was instrumental in bringing law and order.